“Wah!” my mom exclaimed, laughing. “I am 67 years old! I am not a baby!”

My grandmother, on the speakerphone, had been lecturing how my mother’s daughter (namely me) should get breakfast for my mother. In fact, my mother was recovering from a low-stakes surgery and had decided to check into the hospital due to her body’s negative reaction to anesthesia. That reaction runs in our blood, because I remember how horrible it could be.

My mom countered my grandmother again saying that she felt sick and couldn’t even the hospital’s entree—soup. Just a few sips of milk and water. She doesn’t need me to bring breakfast.

I lost the Chinese words then. I didn’t know how to say — if she doesn’t want to eat, then I won’t make her eat. She’s old enough to know. Plus she’s under a hospital supervision, so the care team will jump in if something’s awry. I wanted to say that I wasn’t worried.

My grandmother continued scolding me. I had visited my mom even though the prognosis was that she was barely going to be in the hospital for long. In the morning, I received messages from my dad—sent via group text to my mom, my sister and me—everything is great. surgery a success. My mom, especially, has always been super practical and straightforward.

When I learned to drive, my dad acted like the typical dad teaching a teenager to drive. 100 feet? Too close! Did you see the stop sign? Did you see the car? Did you see the turn? It was horrible.

But similarly, learning to drive with my mom was also horrible. But different. Why are you going so slow? Go faster! Don’t let them cut you off! And a proverb—that to this day, I am not sure if she made it up or it came from classical Chinese literature—don’t block the world from turning. It was teeth-grinding and all of this made me hate driving for years.

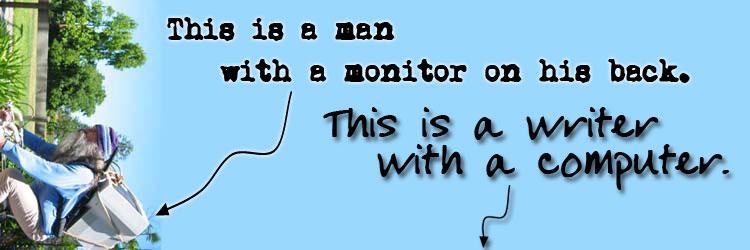

And yet. Here I was in the hospital room with my mom. I had a long history as an adult in barely visiting family members in the hospital. Yes, my schedule conflicted. Yes, it was too out of the way. But I also felt partially distant from them—not just because of the language, but because of how they want to be seen. Did they want me to remember them as partial people, now stricken on a hospital bed? I personally just wouldn’t. I would rather craft the persona I was through my computer and writing.

“Just tell her that you will,” my mom said in English and smiled.

So I did. In that moment, I realized what the nagging meant. For many years, due to my grandmother’s progressing age, she has lost the energy of her youth. She is taken care of by my mom. Like a baby. But here’s a moment with my mom, recovering from surgery wincing from pain and mind clouded with painkillers, that my grandmother had a chance to be a mother again. To have the respect and authority.

When I walked into my mom’s room, I declared that I had arrived. I had read her texts that she was feeling “bad” and couldn’t eat. So I brought my own solution—candied ginger—which had always helped me when carsick and seasick. “It’s from Thailand,” I said, handing the bag of my treasured bits to her. “It’s high quality.”

At the end of our visit—a round of Facetime with my sister and my dad (and some finagling brushing teeth from bed), she leaned back and said, “I feel so much better now.”