“Did you see the car?” my dad said. “Did you see it?”

Not yet sixteen, I stared over the steering wheel and grumbled that yes I did see the car. That is, the car that was more than 100 feet away from me. Once again, I started sulking as I practiced driving. As a highly sensitive teenager who lacked coordination, any criticism darkened my soul immediately. I hated driving.

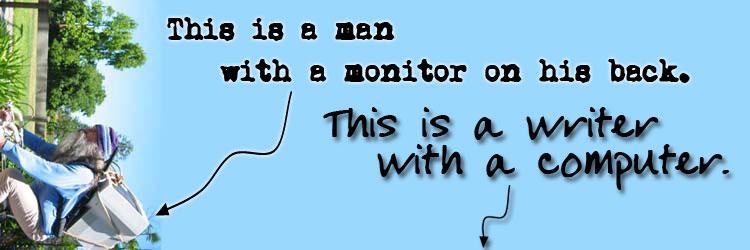

One might say that parents criticize because they care. The bit of chub on my belly. The slowness of my driving (my mom). The speed of my driving (my dad). My hope to be a writer. My desire to be a public speaker, a performer on stage. My inability to maintain an organized room and desk. You know, all because my parents didn’t want me to be disappointed.

Of course, like many teenagers, I aged out and figured out my own life. In the more than ten years of my life, I have figured out how I want to live (dessert first), how I drive (make other people drive for me), and how I want to organize my room (I am happy with messy). I matured and understand why my parents said the things they did even though there are moments where I remember the sting of the words.

And the funny thing is that recently as I watched my dad drive a rental car with sixty-seven-year-old eyes with cataracts, I told him my memory of practicing driving while he sat in the passenger seat. I recalled how all those hours in the driver’s seat with a parent in the car were the worst hours in my teenage life. I succeeded in getting a driver’s license (partly because at that time, I believed that a driver’s license was a necessary part of being an American teenager and I had no intention of missing out), yet driving itself was miserable. But as I watched my dad struggle with the backing up and parallel parking, he admitted his guilt from those hours. He didn’t remember exactly what he said, but he did remember the guilt. To my surprise, he apologized. I was stunned and didn’t say anything. At that moment, I wanted to criticize how slow he was driving, nearly 15 mph below the speed limit. The fact that he couldn’t figure out how to shift from R to D, always skipping to P. Or the fact that he lost the ability to parallel park using the sideview mirrors and twisting the wheel at the right time. It might be because he had a rearview camera in his current car and that it came with parallel parking guides, but it was obvious that his age took its toll. When desperation edged in his voice, he pushed open the drivers door to declare defeat, but Chris intervened and calmly coached him through the parking.

“Turn all the way to the left here,” Chris said watching the sideview mirror. “Now, back up. Back up. Back up. Now straighten. Okay. You did it.”

I could only remember my parents as they are and as they have always been.