I once told a counselor about how I couldn’t understand why I desired so much to be onstage. That when I watch a TED talk, watch a band perform, or watch a comedian, I am instantly compelled to be up there.

Because it doesn’t match my reserved, quiet personality.

“It’s because you want to express yourself,” she answered.

Is that really my way of expression? As writing (or even blogging) has always been my preferred form of expression. It’s not that I want to be the light of the party all the time. I want to have a defined moment, a defined act to be stage. I want to be the star.

Public speaking, like for many, has always been terrifying for me. Witness how nobody in class could hear me speak when I gave a presentation—my voice was tiny and terrified. But I would give it my best with a clear idea of what I wanted to present. I never wanted to be like the “quiet people” who I always perceived as lacking ideas. Or is it that I believe that the loudest, as common in American culture, is the one who grabs the attention and express themselves?

By the time I got to graduate school, my fear of public speaking had subdued. I had accepted the fact that fear was unnecessary (although fear of being judged was another thing of in itself). Somehow I had made the decision that everybody was terrified of public speaking and those who actually attempted speaking, I realized that I could be no worse than them. It might be a superiority complex, but I really believed that the worst thing that anybody could do was say nothing at all.

So when an opportunity popped up for me to host the ice cream eating contest at the ice cream festival, I jumped for it. Sure, it offered an opportunity to promote my book. But even though the spirit of the ice cream eating contest was bad taste and also conflicted with the mission of my book (my recommendation is to have GREAT ice cream in moderate amounts; to travel far and wide to experience those scoops where taste not volume prevails), I wanted to do it. I had admired George Shea from Nathan’s Hot Dog Eating Contest on Fourth of July for some time and that’s exactly what thought that I would do.

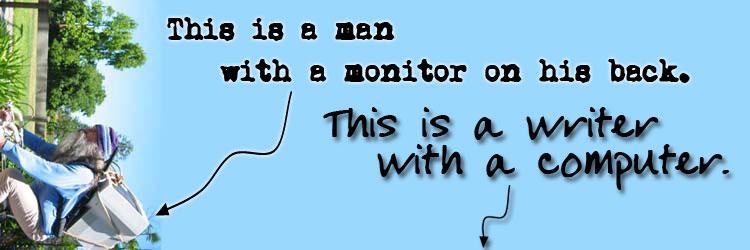

So I prepped. Writing lines. I studied announcers. I brainstormed quotes. And then when the time came when the food park owner handed me the microphone (after I did the “test test” check), I began. I couldn’t match George Shea on my first time as emcee. And yes, I bolted to my backup instead of giving color commentary. But once the competitive eating began, I found myself screaming and yelling. What is cheering and egging competitors if you can’t be heard. And the crazy thing is, people could barely see me over the tops of heads, I felt like it was awesome. Nobody staring at me. Just everybody hearing a shrill voice announcing the winners of the 2016 ice cream eating contest.